“... the details of the room began to slowly emerge from the darkness. There were strange figures of animals, statues and gold - gold shimmered everywhere! For a moment—that moment seemed like an eternity to those behind me—I was literally speechless with amazement.

I believe that most archaeologists will not hide the fact that they feel a sense of awe, even bewilderment, entering a chamber that was locked and sealed centuries ago by pious hands. For a moment, the notion of time as a factor in human life loses all meaning. Three, maybe four thousand years have passed since the last time a human foot stepped on the floor on which we stood, but until now everything around was reminiscent of life that had just stopped: a chest half-filled with lime at the very door , an extinguished lamp, fingerprints on fresh paint, a funeral wreath on the threshold ... It seemed that all this could have been yesterday. The very air that has been preserved here for tens of centuries was the same air that was breathed by those who carried the mummy to the place of its last rest. Time vanished, erased by many intimate details, and we felt almost sacrilegious."

Thus begins the story of Howard Carter's direct opening of Tutankhamun's tomb, the largest archaeological find of the XNUMXth century, which became a worldwide sensation and inspiration for artists, architects and jewelers. However, Egyptomania captured Europe long before the opening of the tomb, or rather, the fascination with Egypt never passed.

For the first time, interest in the Egyptian tradition arises in ancient Rome. The conquest of Egypt and its transformation into a Roman province, the holding of a triumph and the bringing of trophies influenced the spread of Egyptian motifs in Rome. But none of the events of those years had such significance for art and culture as the tragic love story of Antony and Cleopatra. It, although fairly romanticized, became the most common subject of Egyptomania and inspired prominent artists, writers, poets, composers, choreographers, etc. for many centuries.

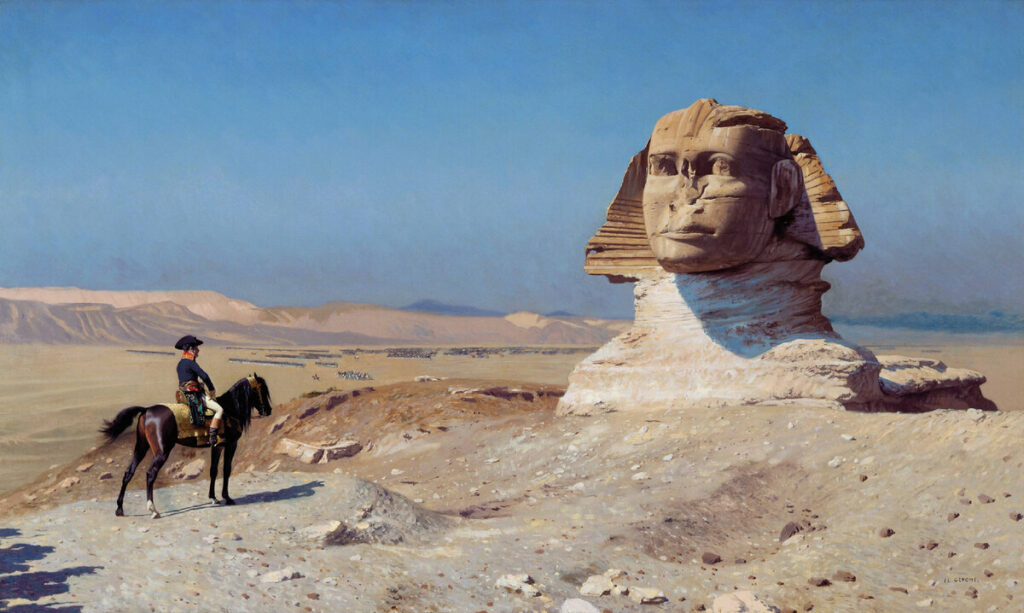

The next important milestone in the history of the study and revival of the art of Ancient Egypt is the Egyptian campaign of Napoleon Bonaparte (1798 - 1801). From a military point of view, he was unsuccessful - Napoleon was defeated, but for science and art, this campaign was of great importance.

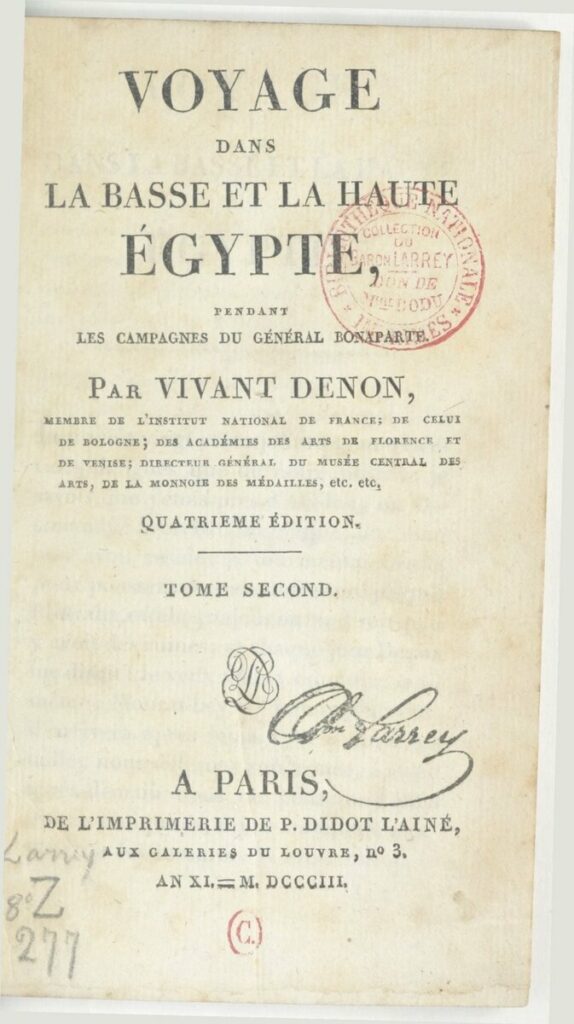

In 1799, the Rosetta Stone was discovered, the deciphering of which by Champollion gave a serious impetus to the development of Egyptology. In addition, following the results of a scientific expedition organized by Napoleon, scientists published a monumental ten-volume Description of Egypt (1809-1829). Another significant work was the book of one of the participants of the expedition - the artist (and in the future the first director of the Louvre) Dominique Vivant-Denon "Journey in Upper and Lower Egypt" (1802), accompanied by a large number of his own sketches of the monuments of Ancient Egypt. After its release, Europe was swept by the first big wave of Egyptomania - the use of Egyptian motifs became a characteristic feature of the Empire style that was dominant at that time. Jewelers also responded to the new fashion, and soon Egyptian-themed jewelry filled the shop windows on the busy streets of Paris.

The next wave of Egyptomania was provoked by systematic excavations begun by French Egyptologists Auguste Mariette and Gaston Maspero in the second half of the 1859th century, as well as the construction of the Suez Canal in 1869-1867, headed by a French joint-stock company. Two years before the completion of construction, interest in Egypt was so great that at the World Exhibition of XNUMX in Paris, a stunning Egyptian pavilion appeared, which made a strong impression on visitors - through it, many for the first time discovered the mysterious charm of a distant ancient country. This pavilion was built to display the collection of archaeological finds of the Bulak Museum (now the Egyptian Museum in Cairo), but in addition to antiquities, the exhibition featured Egyptian-style jewelry created by Gustave Beaugrand, as well as jewelers from Boucheron, Mellerio and others.

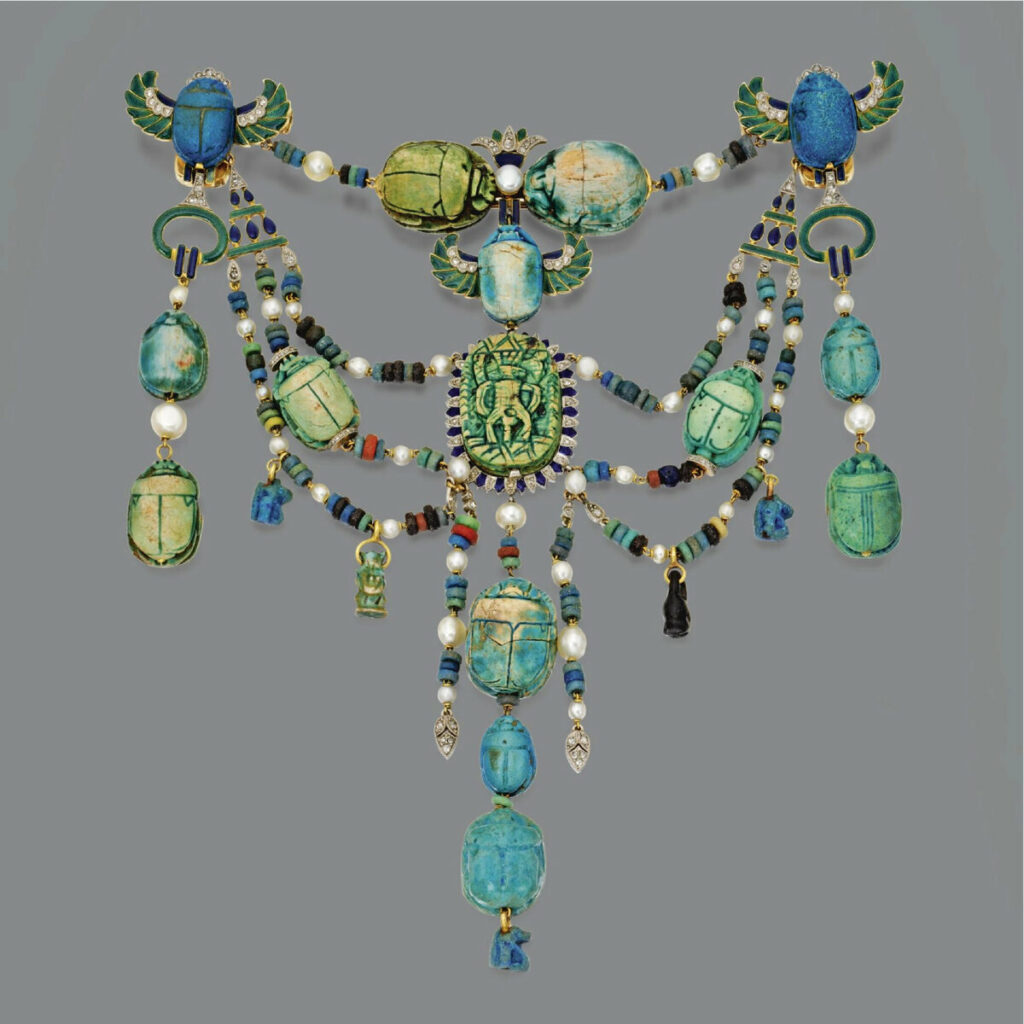

From that moment on, the passion for Egyptian-inspired jewelry spread throughout the continent, and many famous jewelers, including Alessandro Castellani, Carlo Giuliano, Eugène Fortenay, began to create jewelry in the so-called "Egyptian Renaissance" style. True, the new style can only be called a “revival” conditionally. Despite the fact that the jewelers took Egyptian themes and motifs as a basis, they did not try to imitate the ancient masters, to revive the style. Modern decorations were eclectic variations on the ancient Egyptian theme, distinguished by complexity, even some excess, which, in general, did not contradict the art of historicism, which has the same features, especially in its late phase.

Continuous research and amazing finds increased interest in the art of Egypt at the end of the 1880th and especially at the beginning of the 1905th century, when a number of important discoveries were made. In the 1908s, Gaston Maspero begins clearing the temples of Luxor and Karnak, in 1912-XNUMX Edward Ayrton discovered the tombs of the pharaohs in the Valley of the Kings, and in XNUMX Ludwig Borchardt finds a bust of Nefertiti, to name but a few of the landmark discoveries of that period.

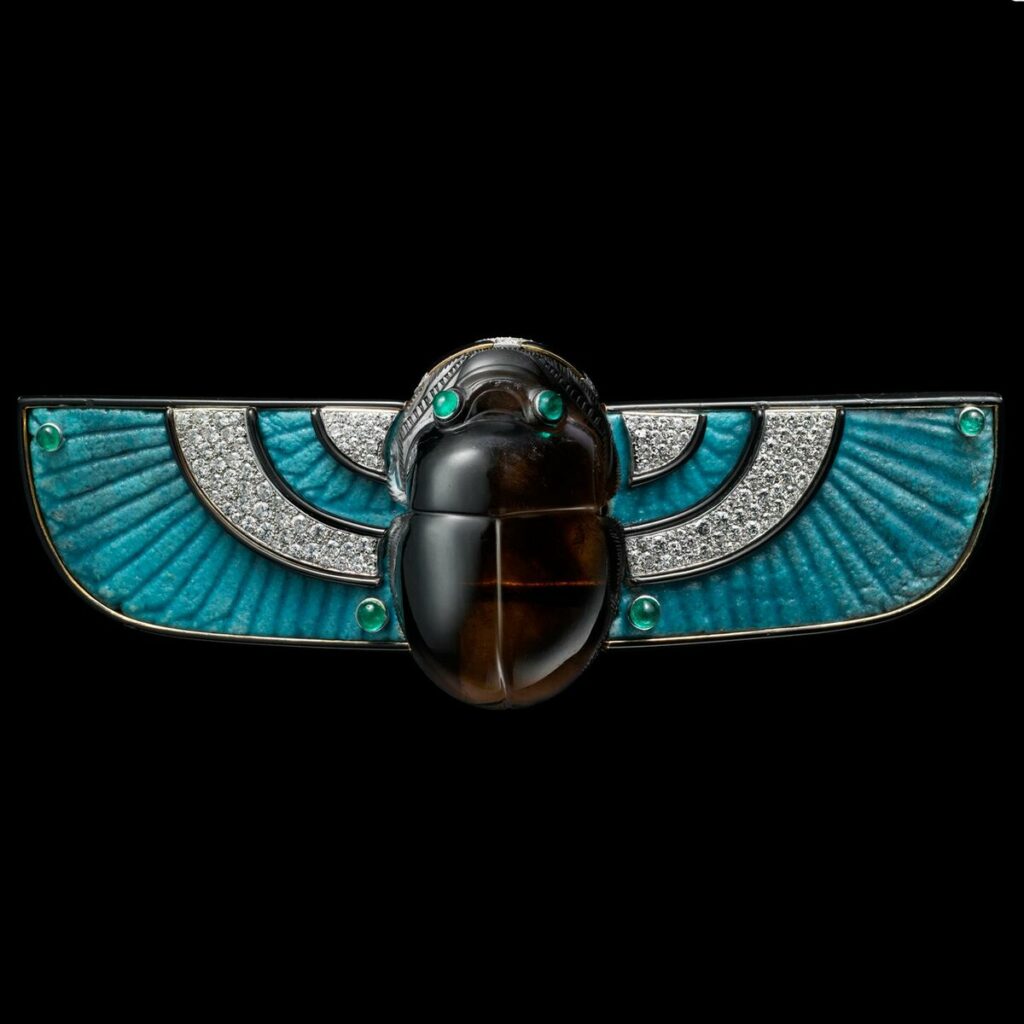

In the modern era, Egyptian motifs were modified in accordance with the new fashion. Mascarons received cute angelic faces, the wings of scarabs became more dynamic and graceful, and the forms of jewelry were often built on the basis of the traditional “scourge strike” line. The modern “Egyptian Renaissance” was vividly embodied in the jewelry art of such significant masters as Rene Lalique, Georges Fouquet, Lucien Gautret and others.

And so we come to where we started. Howard Carter's discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb exactly 100 years ago in 1922 was the culmination of Egyptomania around the world. The stunning arts and crafts found in the interior of the tomb, as well as the jewelry and the legendary golden mask found on the mummy itself, caused such a stir that the Egyptian style became one of the key stylistic sources of Art Deco.

Well, the first to react to the archaeological sensation, of course, were the jewelers. Since that same year, 1922, renowned jewelery houses such as Cartier, Tiffany & Co., Lacloche Freres, Van Cleef & Arpels have been creating exquisite Egyptian-inspired gems to meet the skyrocketing demand.

Cartier were probably one of the main creators of Egyptian Revival jewelry. Since 1910, long before the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb, the firm's jewelers have been making jewelry using the Description of Egypt and the Grammar of Ornament published in 1856 as visual sources. In addition to rethinking the Egyptian motifs borrowed from the Grammar, Cartier often used authentic Egyptian antiquities in their jewelry. The largest Parisian antiquarians supplied Louis Cartier with artifacts from Egypt, and these miniature treasures in a precious frame made of gold, diamonds and other precious stones made an incredible impression on noble customers. With the advent of Art Deco and the discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb, Cartier, like other firms, rethinks the Egyptian style and interprets it in the spirit of the new time.

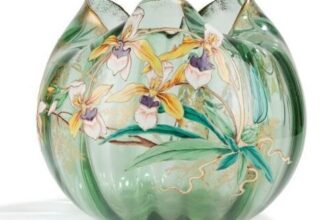

Tiffany & Co. also brought their own unique style to the Egyptian Renaissance. Louis, the son of the founder of the company, Charles Tiffany, was fond of many areas of art and in 1893, after long experiments with stained glass, he discovered a new type of glass - favril. It had a luxurious iridescent effect on the surface, which Louis achieved by treating molten glass with metal oxides. Favril glass jewelers Tiffany & Co. created wonderful iridescent beetles and encrusted them in a variety of art objects. But besides this, the jewelry company has created many interesting jewelry in the style of the "Egyptian Renaissance".

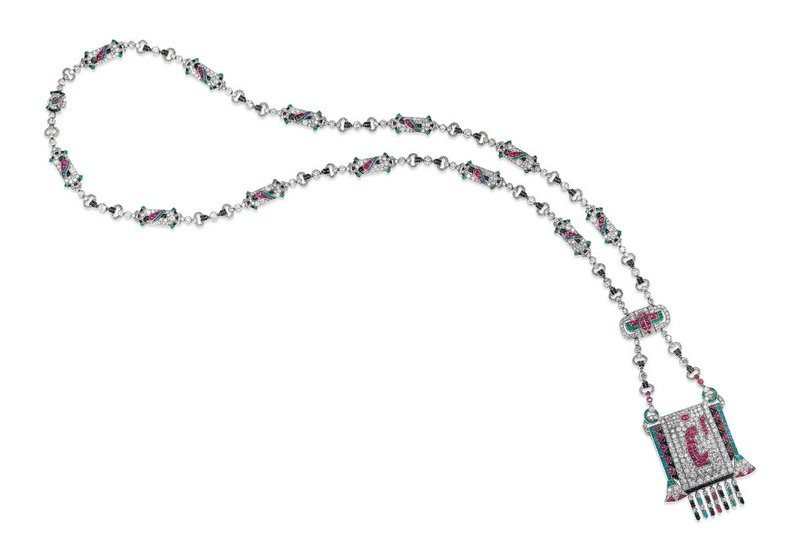

The last two jewelery firms that we will look at in this article, Lacloche Freres and Van Cleef & Arpels, were similar in their approach to working with Egyptian heritage. Both firms used platinum as the basis for jewelry created in the form of a mosaic of precious stones. Traditionally, diamonds served as a background against which images of ancient Egyptian people, birds, animals and flowers were laid out from emeralds, rubies and sapphires. Their images were borrowed from paintings and reliefs in Egyptian temples. Perhaps it was Van Cleef & Arpels who first paid attention to such everyday ancient Egyptian subjects as catching fish and birds, or playing the harp and board games.

Lacloche Freres works in the same manner, but in 1925 he creates a unique bracelet in the spirit of futurism, where not only the symbols and motifs of Egyptian art are very skillfully combined, but also the stones from which the composition is built. The jewelry firm turns to a rather unusual, but very effective combination of precious and semi-precious stones. As in other works, diamonds are used as a background, but instead of rubies, emeralds and sapphires, jewelers take turquoise, black pearls and mother-of-pearl.

With the end of the Art Deco era, Egyptian passions subside, but several times interest in this ancient country returns, first in the 1960s, when the legendary film "Cleopatra" starring Elizabeth Taylor was released, and then in the 1980s and 1990s.