Bibi van der Velden uses natural materials in her jewelry, including this bracelet made from recycled gold and scarab beetle wings harvested from a farm in Bangkok where the scarab beetle is grown as a delicacy.

When Brazilian designer Ara Vartanian tells his clients to "buy the best," he doesn't mean the best jewelry. He means ornaments that are useful.

Mr. Vartanian is one of a growing number of independent jewelers creating trends that go beyond mere style or design. He focuses on materials: he uses gold mined in environmentally friendly conditions.

All of this is part of a movement to take jewelry beyond mere decoration and give it meaning through its contribution to culture and the preservation of the Earth.

But stones mined by miners who are reviving rainforests destroyed by their mining, or investing in clean water or schools for their communities, inevitably cost more than stones from other mines.

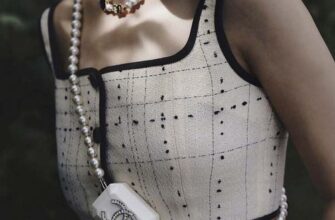

Dutch designer Bibi van der Velden, who works with recycled gold and often incorporates natural materials into her designs, says: “In the business we are in, it is important that we improve the way things are made and people’s livelihoods.”

Below, three sustainable designers share their stories.

Bibi van der Velden

Flora and fauna play major roles in Bibi van der Velden's designs, such as her Alligator Bite earrings, gold alligators that tuck their earlobes in their mouths while their tails dance below; or Monkey Ring in a Ring, where monkeys with brown diamonds are circling around the finger, and the other ring is adorned with a golden banana.

The designer also values nature in her materials, including scarab beetle wings harvested from a farm in Bangkok where the insects are grown as a delicacy, recycled gold and mammoth tusk she purchased 15 years ago. “The tusk has many of the properties of ivory,” she said in a recent telephone interview, “but does not harm a living animal. Also, you are actually saving the tusk, because otherwise, if it is exposed to oxygen, it will break down.”

Much of Ms. van der Velden's work is made to order, which often allows her to alter or resurface stones from a client's existing pieces for a new design. “I love anything that can be put into a new context and given new life,” she says.

Ara Vartanyan

In 2019, Mr. Vartanyan created the Mining Conscious Mining Initiative, standards to encourage social responsibility in the mining industry, which he proposed to other companies to adopt.

His inverted diamonds, now a registered trademark, are literally this: brilliant-cut stones are positioned so that the table, or flat part of the stone, rests against the wearer's skin, with the point pointing upwards. The result is not only ergonomic and architectural, but also an intriguing restructuring of form, refraction and light.

An example is his take on the classic tennis bracelet, a studded, punk-like strand of black, white, or black and white inverted diamonds that illuminates the stones as they pyramid out of the wearer's wrist. Or consider his two- and three-finger rings, which reimagine what a ring on the wearer's hand can be: instead of a single ring with a gem placed on one finger, these rings wrap around two or three fingers, balancing between them with a bold center emerald or rubellite.

The jeweler was born in Lebanon but grew up in São Paulo, Brazil, the son of a mother who was a jewelry designer and a father who was a gem trader. This upbringing gave him an almost instinctive understanding of how cutting and setting a stone can affect a piece of jewelry. It also left him with a deep love for Brazil, where his business is located. This love is manifested in the frequent use of Brazilian emeralds, rubellites and blue tourmalines Paraiba, which are sourced exclusively from Brazil's Cruzeiro, Belmont and Brazil Paraiba mines, which have adopted the ethical and sustainable practice standards of his initiative.

Mr. Vartanian acknowledges that jewelers cannot always know or verify the source of all their stones. But he says he sees progress.

Lula Castillo

Castillo's atelier in upstate New York is nothing like your typical goldsmith's shop. There is no gold here. There are no precious or semi-precious stones here. The Colombian-born designer works exclusively with organic materials from South America: acai seeds, lima beans, bombon beans, Peruvian chirilla seeds, tagua nuts and citrus peels.

“I love gems,” she said during a recent video call. “They come from nature and they are beautiful. But it never occurred to me to use them. Nature itself gives me the material.

Holding the tagua in her hand, she explained her process: she peels the nut, then slices it and knits the pieces together with other beans, seeds, and citrus peels to form roses. She drills centers in other tagua nuts to make retro chain necklaces, some milky white, others dyed in turquoise, crimson or saffron, which Castillo says are inspired by the art and fashion of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo.

Nuit Noire necklace, made from tagua nuts in the form of loops and circles, acai seeds, bombon nuts and organic cotton cord, the techniques she uses are mostly traditional in Latin America, although Ms. Castillo has changed them over the years. For example, unlike artisans in her home country, where the seeds are often polished, drilled and dyed in large batches, she processes them by hand, mixing the dyes herself.

From simple combinations to complex, interwoven layers of form, texture and color, many of her works combine tradition with contemporary trends. For example, her amethyst-hued Purple Rain necklace intertwines jacaranda seed pods and bell-shaped silk cocoons.

Such products go beyond the simple use of sustainable materials; her work also supports a handicraft tradition that is in danger of being lost. “I like to think of myself as an alchemist,” she says. "Everything that passes through my hands must be transformed."